Maryland’s historic homes and farms have often included various domestic and agricultural support structures, sometimes called outbuildings. Some of these outbuildings had very specific functions: one example is the potato house. These structures were built to cure sweet potatoes. (Long-term storage for both sweet and white potatoes, on the other hand, could be in common root cellars.)

The curing process is important for sweet potatoes because it improves their flavor, quality, and longevity. It toughens the skin; heals cuts, bruises, and scrapes; and promotes the conversion of starches to sugars. With a crop that was “cured,” farmers were then able to keep sweet potatoes in storage until market prices were favorable for their sale. The process involved keeping the sweet potatoes in a dry place that was heated to a constant 50 degrees Fahrenheit. This meant that potato houses were heated with a wood, oil, or coal-burning stove through the winter after a fall harvest. The presence of a chimney is a tell-tale sign that an outbuilding is a potato house.

The sweet potato was consumed for subsistence in the United States for many years, especially by poor folk in the South. However, the sweet potato became a cash crop grown in mass quantities in the late 19thand early 20th centuries. While many states grew more sweet potatoes in total than Maryland, it was a very important product on the Lower Eastern Shore in particular.

At least 14 Eastern Shore potato houses are documented in the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties, our statewide repository for information on historic sites, buildings, structures, and objects. This existing documentation is of critical importance, because not many potato houses survive today.

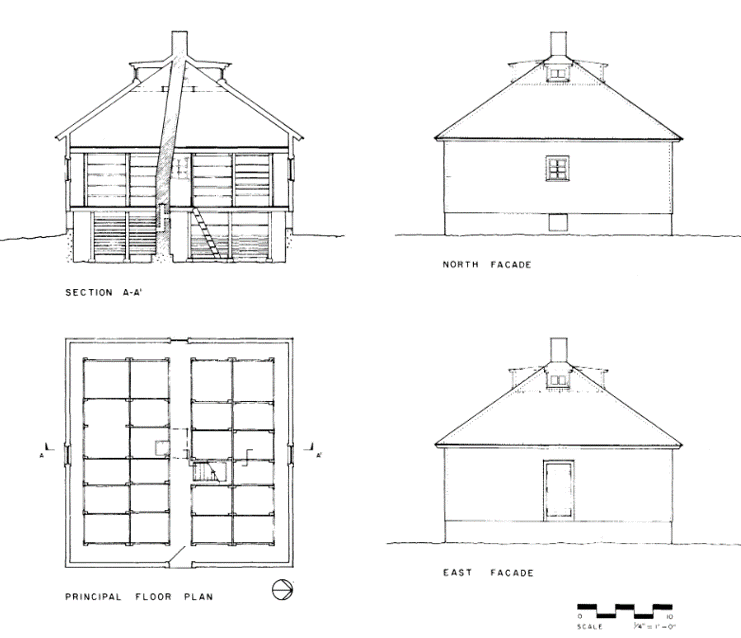

One demolished example is the Andrew Wilson’s Potato House, which was located in the vicinity of Pond Town, an African American community in Queen Anne’s County. It was a square frame building sheathed with weatherboard and topped with a pyramidal roof, which was pierced in the center by a stuccoed chimney stack. There were four shed roof dormer windows, one on each section of the roof. The interior consisted of three levels, a cellar, the main floor, and a loft. The main floor and cellar were divided into rows of bins for potato storage arranged on either side of a central aisle. A narrow secondary aisle circled each floor, providing access to the outer rows of bins. The structure was heated by two wood stoves in the cellar. The potato house was owned and operated by Black farmer and entrepreneur Andrew Wilson. Mr. Wilson rented space in the potato house to local farmers for a set price per bushel.

A surviving example that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places is the Maple Leaf Farm Potato House in Wicomico County. It is one of three documented brick potato houses. This is a large structure, measuring 40’2” by 24’. There are two levels for potato storage, supported by large summer beams and close-set joists to carry the heavy load. The surviving exterior sliding door would have provided additional insulation. This potato house was built around 1920 and owned by Henry Rounds, who transported his sweet potato crop by a two-horse wagon to wholesalers on Mill Street in Salisbury. The Maple Leaf Farm Potato House was relocated to a different farm in 1997 to save it from demolition during the construction of the US 50 bypass.

Because of their significance to Maryland’s agricultural heritage, MHT is working to document more potato houses. If you know of any surviving examples, you can contact Allison Luthern at allison.luthern@maryland.gov to assist with this effort!