By Steven Xavier Lee, Independent Historian

In the ‘War of 1812’, when the British again sought claim of its former American Colonies, Maryland was a major scene. But among its many chronicles, outside of the focus of enslavement, acknowledgement of the patriotism and participation of Maryland’s free African Americans, has been relatively unknown. Indeed, it was the enslaved Black men, who, as property, were more assiduously documented and identified, as they were designated as servants or assistants to the ranking all-white officers of the regiments. Most were recorded by only a single name, such as: “Hamilton, negro, Capt’ servant; Peter, negro, subaltern’s servant”, or “Servant: Moses (to Capt. Tobias Stansburry).”[1] Some of distinction would be listed with their full names. One of the most notable, Samuel Neale, was an enslaved steward assigned to the military surgeon, Dr. William Hammond, of the First Maryland Calvary. Neale was cited for valiantly aiding and carrying all of Dr. Hammond’s medical instruments for him across many Maryland battlefields, including at the Battle of North Point.

But recognition of the free Black men who enlisted and served in the Wars for Independence, has been negligible. They are among the many chapters omitted in Maryland history, on her extensive early free-Black community.

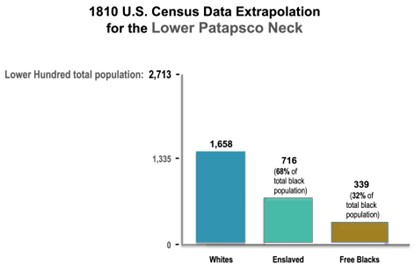

The Battle of North Point in 1814, engaged the Lower Patapsco Neck in Baltimore County, and was the stage of a seminal victory in the ‘War of 1812’. The Lower Patapsco Neck (the peninsula encompassing today’s Canton, Dundalk, Edgemere, Turner Station and North Point), was recorded in the 1810 U.S. Federal Census, with a total population of about 2,713 people .[3] Of that total, 1,658 were white (about 61%); and 1,055 (about 39%) were Black. Of that total Black population, about 339 individuals were recorded as free Black people. Thus, about a third of the Lower Patapsco Neck’s African American population, were free people. Where are their stories?

One of those lost stories must be that of Mr. Nicholas Brice, a member of this free-Black community. The 1810 Census listed him as a head of household, residing in the Lower Neck, with four other free Black persons (presumably his family). That would have made the Brices one of 51 Black families, that the U.S. Census counted, residing in the Lower Patapsco Neck (the ‘Patapsco Lower Hundred’ in 1810). In the course of research, a correlation of 19th century Census data and military records fostered the first identification of a free Black ‘War of 1812’ soldier, from the Lower Patapsco Neck. He is none other than, Mr. Nicholas Brice.

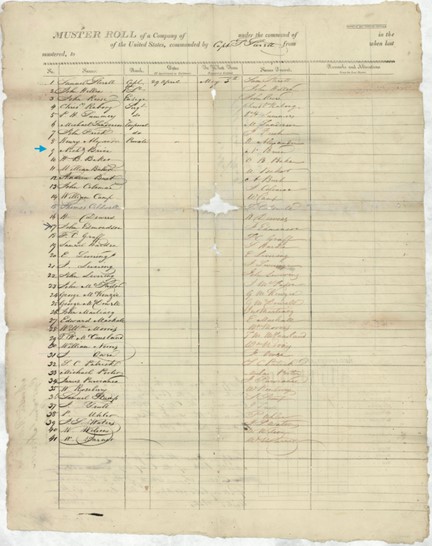

Mr. Brice’s name appears in the 1813 muster and pay rolls, as a Private enlisted in the fifth regiment of the Maryland Militia, serving under Captain Samuel Sterrett. (‘Private’ was the highest rank available to non-white military men of the era of the Wars for Independence, no matter how outstanding their service, i.e. Thomas Carney.)

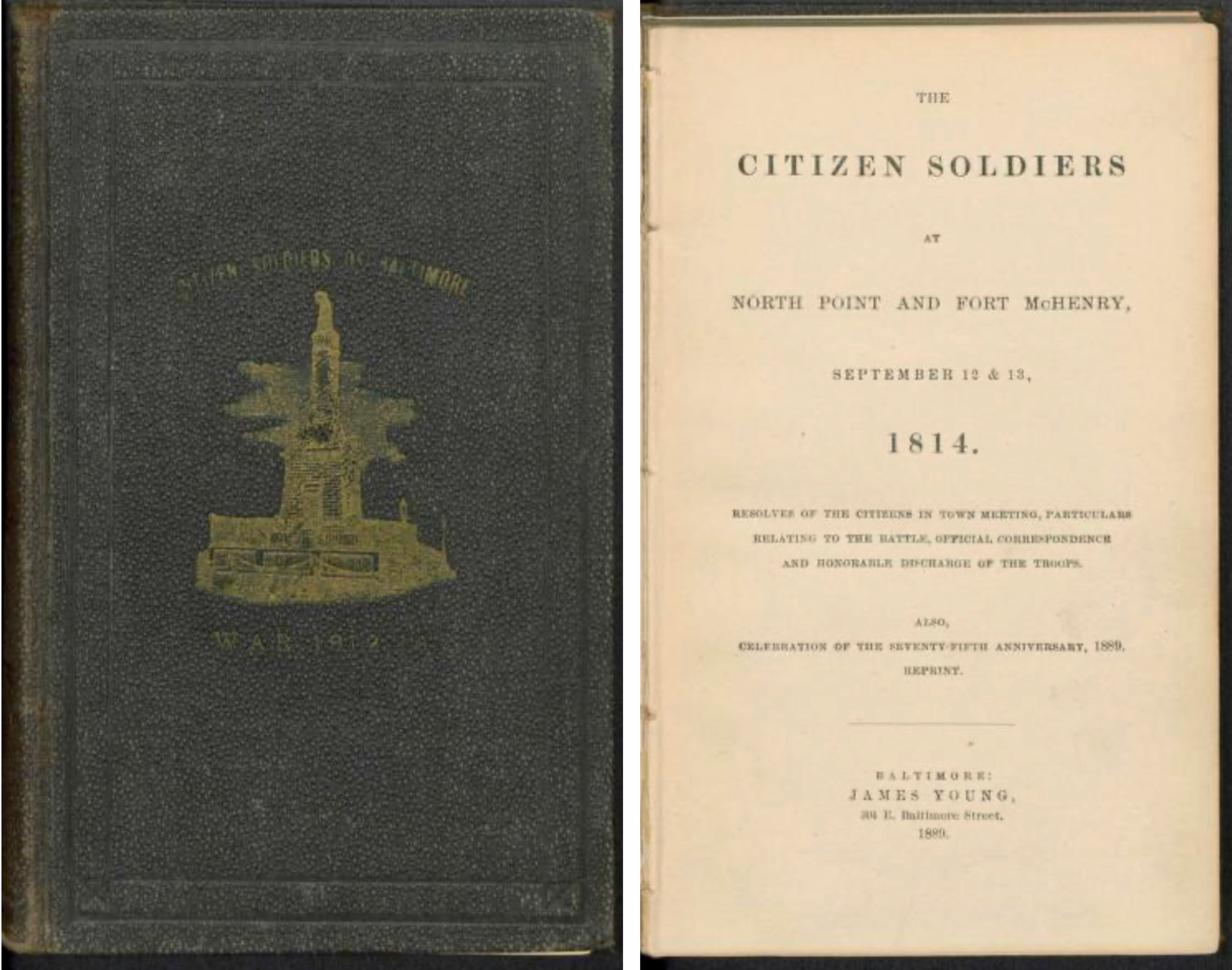

Nicholas Brice is also documented in 1814, still serving with Captain Samuel Sterrett, defending the Lower Patapsco Neck in some of the most intense battle campaigns in the ‘War of 1812’, for Fort McHenry and North Point.

The continued enlistment of Nicholas Brice in the Independent Company of Captain Sterrett, evokes a keener interest into this quintessential Maryland story. Captain Samuel Sterrett (who would later become a Major), was of a prominent Baltimore Town/County Scottish family, many of whom were enslavers. Distinctively, Samuel Sterrett appears to be of a different ethos. He had been an active member of the ‘Maryland Society, for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Relief of Free Negroes, and Others Unlawfully Held in Bondage,’ and was cited in 1791 as the organization’s president. [4] Most likely Captain Sterrett had an established rapport and credibility with the area’s African American community. It is most probable that Mr. Nicholas Brice was not the only free Black gentleman in the Patapsco area to join with Samuel Sterrett when he made the call to arms, recruiting for his Company. Within the list of those 76 men in the 1814 Independent Company of Captain Sterrett,[5] there must be other African American militiamen yet to be so identified.

Home-rooted with his family in the Lower Patapsco Neck, Mr. Nicholas Brice was steadfast in defending his homeland, when the British invaded fomenting division and defection among the American people. But the newly united States remained united with the fortitude and fraternity of its people (Black and white). Nicholas Brice’s contribution is not just one of Black history. It is one of Maryland history. He, like other early Maryland African Americans both free and those enslaved, shared in and were a part of those crucible experiences, some horrid and some noble, that connects all Marylanders. Entering the new epoch of the nation’s Semiquincentennial, perhaps for the first time in 250 years, there will come to be equitably, recognition, inclusion and discovery, of the many free early Maryland African Americans, when presenting Maryland history.

References:

[1] Maryland Militia War of 1812 – Volume 2: Baltimore City and County, page 14 and 75 respectively; by F. Edward Wright; ISBN# 9781680340068

[2] Base map design from Maryland Department of the Environment

[3] The Bear Creek Research Project, ‘American Battlefield Protection Program’ of the National Park Service.

[4] Program of the “Oration Upon The Moral and Political Evil of Slavery”, July 4, 1791,by The Maryland Society, for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Relief of Free Negroes, and others unlawfully Held in Bondage. ‘Evans Early American Imprint Collection’, University of Michigan.

[5] ‘The Citizen Soldiers of North Point and Fort McHenry’, 1889 publication – INTERNET ARCHIVE

Special Acknowledgements:

Dr. Glenn T. Johnston, Stevenson University / Bear Creek Research Project

Owen E. Lourie, Maryland State Archives

Jeni Spamer, MSA Baltimore City Archives