Robert W. Johnson Community Center – Washington County ($150,000) | Sponsor: Robert W. Johnson Community Center, Inc.

Funding will help restore the Robert W. Johnson Community Center – founded as a school for Black children in 1888 before becoming a Black YMCA in 1947 – so it can continue to be a place for community events and educational programming. The RWJCC offers after school programming as well as adult education classes. Funding will support renovation of the community pool, plumbing and electrical upgrades, and other renovation efforts.

Hoppy Adams House – Annapolis ($245,000) | Sponsor: Charles W. “Hoppy” Adams Jr. Foundation, Inc.

Known for spreading soul and R&B music to Black and white audiences, Charles “Hoppy” Adams Jr. was a celebrated African American radio broadcaster with WANN Annapolis. Adams hosted popular concerts at Carr’s Beach, an important venue on the Chitlin Circuit during segregation. In 1964, Adams built this expansive brick ranch-style home within the tight-knit Black community of Parole, on land passed down by his family since 1880. Adams lived in the house until his death in 2005. Funding will support ADA compliance efforts, electrical upgrades, and structural support.

American Hall – Washington County ($250,000) | Sponsor: The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free And Accepted Masons Of Maryland And Its Jurisdiction, Inc.

The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free And Accepted Masons Of Maryland And Its Jurisdiction, Inc. , aims to restore American Hall, which was the meeting place of Lyon Post #31 G.A.R. Making it one of the last surviving meeting places of an African American G.A.R. post in the country. Originally built in 1883, American Hall used to house the fraternal lodge, community meeting space, and a school in the basement. This project aims to rehabilitate the building for further community use with the addition of an exhibit. Funding will support structural repairs, architectural drawings, and a bathroom addition.

Upton Mansion – Baltimore City ($250,000) | Sponsor: Afro Charities, Inc.

Upton Mansion, located in the Old West Baltimore Historic District, was once the home of Robert J. Young, one of Baltimore’s most successful African American real estate developers in the early 20th century. This project aims to restore the mansion as the headquarters for Afro Charities, Afro Archives, and the AFRO American Newspapers. The archives include approximately three million photograms, several thousand letters, back issues of the newspaper’s 13 editions, and personal audio recordings of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. The Upton Mansion will serve as the permanent home and research center for this collection, allowing it to be available to the public. Funding will support new construction of an annex and windows and doors repairs.

Henry’s Hotel – Worcester County ($250,000) | Sponsor: Henry Hotel Foundation, Inc.

Built in the late 1800s, Henry’s Hotel, formerly known as “Henry’s Colored Hotel,” is one of the oldest hotels in Ocean City. It was also the last hotel that allowed African Americans access to the beach during Jim Crow-era restrictions. This project aims to turn the building into a museum and learning center that will educate the public on how African Americans contributed to the town’s development, yet suffered from discrimination under segregation. Funding will support a new foundation, staircase, and porch.

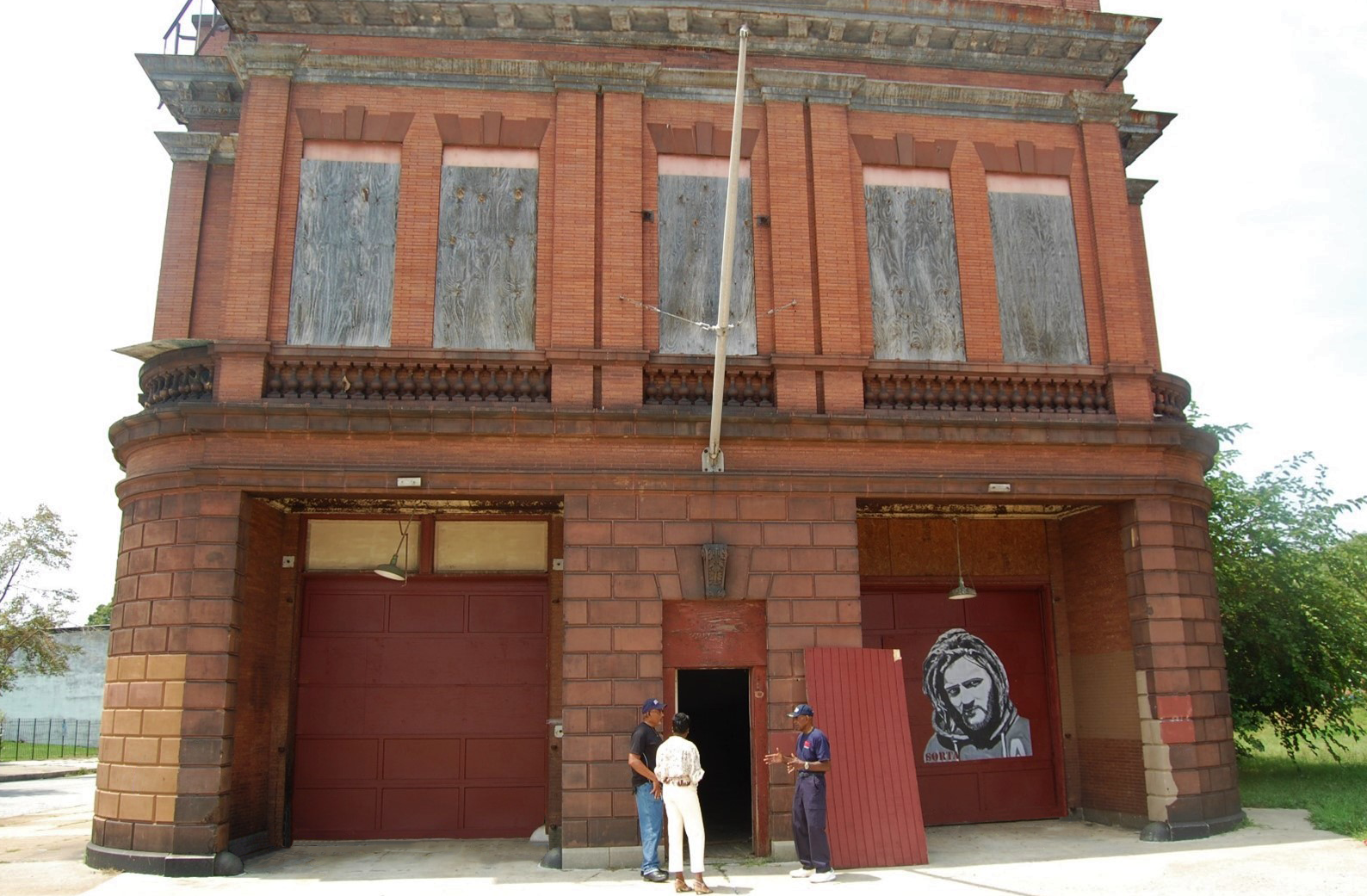

Historic Oliver Community Firehouse – Baltimore City ($247,000) | Sponsor: African American Fire Fighters Historical Society, Inc.

Built in 1905, the historic firehouse in Baltimore’s Oliver neighborhood, Truck House #5, is a two-story structure with two truck bays that will be acquired from the City through the Vacants to Value program and restored as the International Black FireFighters Museum & Safety Education Center. Funding will support exterior rehabilitation including window repairs as well as carpentry and masonry repairs.

Brown’s UMC Multi Cultural Heritage Center – Calvert County ($250,000) | Sponsor: Brown’s UMC Multi Cultural Heritage Center, Inc.

Built in the 1890s, the one-room Brown’s United Methodist Church (UMC) serves as a reminder of the days of segregation and is one of the oldest African American churches in Calvert County. Once completed, the UMC Multi-Cultural Heritage Center will have an exhibit showcasing local history within. Rehabilitation of the cemetery will allow for self-guided as well as guided tours of the cemetery. Funding will support foundation repairs, flooring repairs, and a roof replacement.

Buffalo Soldier Living History Site – Wicomico County ($250,000) | Sponsor: Buffalo Soldier Living History Site Co.

Formerly known as the “Colored Settlement,” the Buffalo Soldier Living History Site will be established on a site, bought in 1898, of former Buffalo Soldier Thomas E. Polk. The site aims to revitalize this dwelling by establishing a museum. Exhibits will include preserving local and state African American military history and holding reenactments. Funding will support selective demolition, structural repairs, and door repairs.

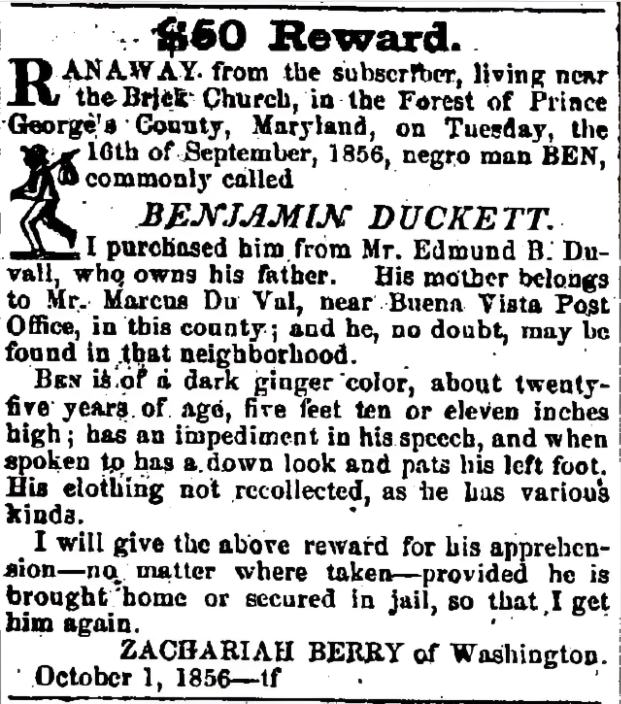

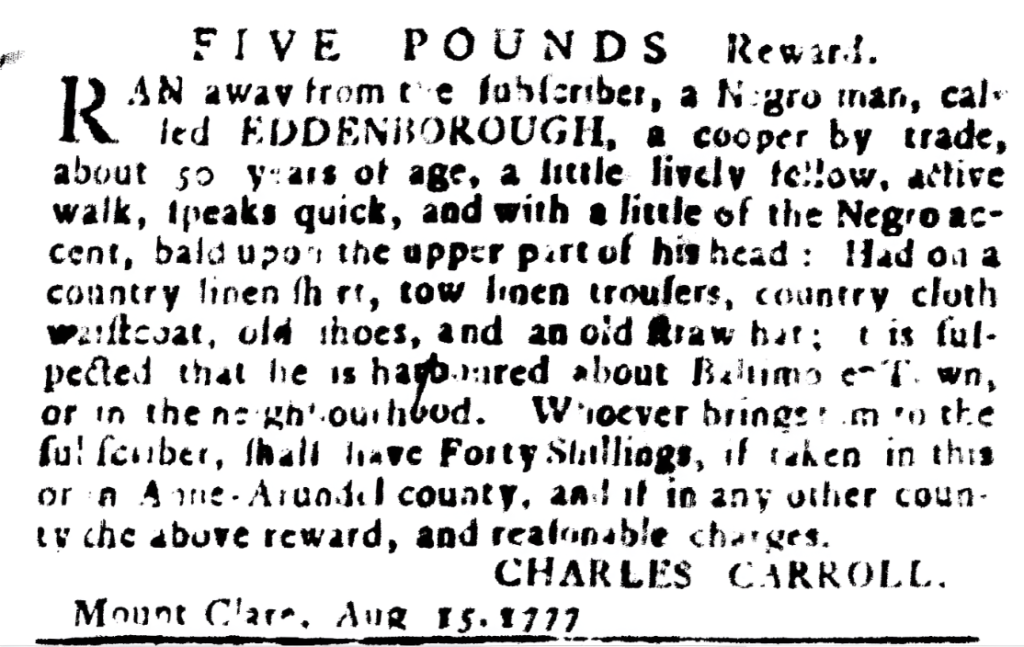

Brewer Hill Cemetery – Annapolis ($250,000) | Sponsor: Brewer Hill Cemetery Association, Inc.

Brewer Hill Cemetery is the oldest Black graveyard in the City of Annapolis. Judge Nichols Brewer originally owned the cemetery and used it to bury those he enslaved, his servants, and other employees of the Black community. Among the interred are people with significant stories, such as Mary Naylor, who maintained her innocence until her hanging in 1861 for allegedly poisoning her master. Funding will support overall cemetery conservation efforts including fence repairs and masonry repairs.

The Bellevue Passage Museum – Talbot County ($250,000) | Sponsor: Mid-Shore Community Foundation, Inc.

The Bellevue Passage Museum aims to shed light on African American culture and heritage by showcasing the untold story of Bellevue’s self-sufficiency and how they thrived and contributed to the state’s economy. Bellevue was once a self-sufficient African American community that initially was centered around employment provided by the W.H. Valliant Packing Co., established in 1895. The museum is on a mission to conserve the African American maritime story that is largely being erased and to become a center of entrepreneurship to the younger generation and a place for community gatherings. Funding will support construction of a new annex, site work, and accessibility improvements.

The Fruitland Community Center – Wicomico County ($203,000) | Sponsor: Fruitland Community Center, Inc.

The Fruitland Community Center is housed in the former Morris Street Colored School, constructed in 1912. Since 1985, the building has been used as a community center that assists low-income youth in Fruitland by providing an after school program that seeks to provide educational activities and teaching African American history. Funding will support structural repairs, carpentry and metal repairs, as well as mechanical and electrical upgrades.

Grasonville Community Center – Queen Anne’s County ($250,000) | Sponsor: Grasonville Community Center

Grasonville Community Center aims to connect and share the African American experiences in the community by providing a place where one can go to engage in programs that offer mentorship, physical and mental health guidance, and other resources. Future plans include providing an after school and summer program that will use the Center’s Black History Library and Health Room to teach history to young visitors. Funding will support kitchen upgrades, interior and exterior rehabilitation, and window repairs.

Malone Methodist Episcopal Church – Dorchester County ($250,000) | Sponsor: Harrisville/Malone Cemetery Maintenance Fund, Inc.

Free-born families began settling in Malone in the late 18th century. Malone Methodist Episcopal Church began serving this African American community when it was built in 1895. The church and community have links to Harriet Tubman’s extended family, who lived in the area and are buried in the cemetery adjacent to the church. Funding will support floor and roof repairs, exterior rehabilitation efforts, and finishes and painting.

Bryan’s Chapel and Cemetery – Queen Anne’s County ($250,000) | Sponsor: Bryan’s United Methodist Church, Inc.

Bryan’s Chapel was founded in the 1800s and is the second oldest African American Methodist Episcopal Church in the United Methodist Peninsula-Delaware Conference. The Bryan’s Church congregation helped establish a school, a beneficial society, and the county’s NAACP Chapter. Shortly after the Civil War, the congregation helped establish an African American school in 1866 that a Rosenwald school later replaced. Funding will support ground penetrating radar, headstone conservation, and foundation and masonry repairs of the Chapel.

Locust United Methodist Church – Howard County ($233,500) | Sponsor: Locust United Methodist Church

Locust United Methodist Church was founded in 1869 by a group of formerly enslaved people in what was then called Freetown (Howard County). The predominantly African American congregation has been active for more than 150 years and in its current structure since 1951. This project will renovate and add an addition to serve as the home of the current history collection and stories of community members descended from the church’s founders. Funding will support selective demolition, new construction of a pavilion, and interior rehabilitation efforts.

Two Sisters’ Houses (Caulkers’ Houses) – Baltimore City ($250,000) | Sponsor: The Society For The Preservation Of Federal Hill And Fell’s Point, Inc.

Built around 1979, the Two Sisters’ Houses (or Caulkers’ Houses) are the only extant survivors of a wooden building type that was once the predominant housing stock for the lower and middle classes in Baltimore. These once-common buildings were vitally important to the early architectural and physical character of the port city of Baltimore. The buildings housed many working Baltimore residents, including African-American ship caulkers Richard Jones, Henry Scott, and John Whittington from 1842 to 1854. Funding will support fire safety improvements, carpentry and masonry repairs, and mechanical and electrical upgrades.

The Yellow/Hearse House – Kent County ($200,000) | Sponsor: Kent County Public Library

The Yellow/Hearse House was originally built in 1906 and served most of its existence as the only funeral parlor for those of African descent in Kent County. The Hearse House represents the rich history of Kent County’s African American-owned businesses. This project aims to increase heritage education and tourism in the Calvert Street business and residential corridor, highlighting the Walley family and the neighborhood in which their business, the funeral parlor, existed. Funds will support insulation installation, bathroom and kitchen upgrades, and framing repairs.

Jones & Moore Luncheon/Bambricks Cards & Gifts – Dorchester County ($138,000) | Sponsor: Alpha Genesis Community Development Corporation

The Jones & Moore Luncheon/Bambricks Cards & Gifts aims to renovate a two-story commercial property located at the corner of Cannery Way. The rear parking lot of the building is now the viewing area for the nationally acclaimed “Take My Hand” mural of Harriet Tubman. Rehabilitation of the building will help bring new arts and cultural programming as well as other business ventures into the district. Funding will support gutter and downspout repairs, window and door repairs, and roof replacement.

Mt. Calvary United Methodist Church – Meeting Hall and Cemetery – Anne Arundel County ($186,000) | Sponsor: Mt. Calvary Community Engagement Incorporated

With grant funds supporting both cemetery and building preservation efforts, Mt. Calvary United Methodist Church will establish a heritage center in its Meeting Hall to share the histories of the local African American community in Arnold. The Hall served as the original Meeting House for the African American community between 1832-1842. By preserving the cemetery, where Civil Rights activists and veterans are buried, the church can provide further educational opportunities in addition to programs in the Meeting Hall. Funding will support ground penetrating radar, site work, and foundation and masonry repairs.

Ridgley Methodist Church and Cemetery – Prince George’s County ($111,000) | Sponsor: Mildred Ridgley Gray Charitable Trust, Inc.

Ridgely Methodist Church is one of only two buildings that remain in the small rural African American community of Ridgely, founded by freedmen around 1871. Historically, the church also functioned as a school for the local Black children. By undergoing rehabilitation efforts, the church hopes to increase the awareness of African American history through special programs, lectures, and tours. Funding will support cemetery conservation efforts, ground penetrating radar, and a fence installation.

Scotland African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Zion Church – Montgomery County ($104,000) | Sponsor: Scotland A.M.E. Zion Church

Scotland A.M.E. provides an opportunity for the public to continue to learn the local history of the predominantly African American Scotland community that has persisted for over 115 years as a congregation and 150 years as a community. The project will provide an opportunity for the public to continue to learn the local story of the predominantly African American Scotland community through interpretive panels and stories shared by congregants in public programs Funding will support foundation repairs, lifting the building, and stabilization efforts.

Bushy Park Community Cemetery – Howard County ($63,500) | Sponsor: Bushy Park Community Cemetery, Inc.

Bushy Park Community Cemetery was historically part of farmland worked by the enslaved populations of Howard County. The cemetery is the burial location of many enslaved and freed individuals, United States Colored Troops soldiers, and Civil Rights leaders. The cemetery’s restoration, supported by grant funds, will allow for educational opportunities centered on those interred there. Funding will support cemetery conservation efforts, ground penetrating radar, and vegetation removal.

James Stephenson House, Enslaved Quarters – Harford County ($119,000) | Sponsor: Maryland Department of Natural Resources

The James Stephenson House, and its associated dwellings, was originally built at the turn of the eighteenth century. The house and quarters are located within Susquehanna State Park. When the quarters building was originally surveyed in the late 1970s, it was mistaken for a smokehouse. The building, now one of the few documented freestanding quarters on public land. Funding will support roof, window, and door repairs, carpentry and masonry repairs, and chimney and shutter repairs.

American Legion Mannie Scott Post 193 Building – Caroline County ($250,000) | Sponsor: The American Legion, Department Of Maryland, Mannie Scott Post #193, Incorporated

Mannie Scott Post No. 193 was chartered in 1947 by the American Legion – a United States veteran association and nonprofit organization created to enhance the well-being of American veterans, their families, military members, and their communities. Post No. 193 is Caroline County’s only African American active post dedicated to those who have served in active duty military in all branches of America’s Armed Forces. Post No. 193 offers programming to the local community that promote justice, freedom, and democracy. Funding will support insulation installation, bathroom and kitchen upgrades, and siding repairs or replacements.