By Dr. Brenna Spray, MHT Outreach Coordinator

In honor of International Underground Railroad Month, we want to share some of the Maryland Historical Trust (MHT) easement sites included in the National Park Service’s Network to Freedom, an effort that aims to “honor, preserve and promote the history of resistance to enslavement through escape and flight.” Across the United States, from Maine to Florida and Virginia to Kansas, there are over 740 sites, facilities, and programs; a few even reach as far west as Colorado and California! Maryland hosts nearly 90 of these 740 sites, and MHT holds preservation easements on nine of them, working with property owners to safeguard them in perpetuity.

Sotterley Plantation (St. Mary’s County)

Sotterley Plantation began in 1703 with James Bowles, the son of a wealthy London merchant who traded tobacco, lumber, livestock, and enslaved people throughout England, West Africa, and the Caribbean. In September of 1720, the Generous Jenny delivered 218 enslaved men, women, and children to Bowles, who had purchased them from the Windward Coast (modern day Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Ivory Coast) and from the Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast (modern day Ghana). It remains unclear how many of these enslaved individuals stayed at Sotterley, as on Bowles’ death in 1727, his widow and daughters inherited 41 enslaved people. James Bowles’ daughter, Rebecca, married George Plater II, initiating four generations of Plater ownership at Sotterley Plantation (Our History – Sotterley, 2018).

Between the 1780s and 1790s, those enslaved by the Plater family made numerous attempts to seek freedom, including Clem Hill and Towerhill, whose attempts put Sotterley in the Network to Freedom. Clem Hill, described as ‘exceedingly artful’ in his runaway ad, left Sotterley in November 1784 (Plater, 1784). Enslavers in North America specifically targeted western Africa, particularly the Gold Coast, when searching for artisans; is it possible that Clem was descended from the original group of enslaved brought from the Gold Coast to Sotterley (Holloway, 2005, pp. 34, 42–44)? In January 1786, a 25-year-old man named Towerhill left Sotterley, likely aiming for Baltimore – a popular destination for freedom seekers, due to transportation options and the large free Black population (Plater, 1786). Is it possible that he reached the city? We will never know for sure, but Towerhill of Sotterley left two years before the birth of a freeborn man named Towerhill who lived in Baltimore City, according to his 1809 certificate of freedom (Certificate of Freedom for Towerhill, 1809).

Port Tobacco Courthouse and Jail (Charles County)

In July of 1845, 75 enslaved men embarked from Charles County on a journey to find freedom in Pennsylvania, led by Mark Caesar and Bill Wheeler, in a movement now known as the Port Tobacco Escape of 1845. While traversing southern Maryland into Montgomery County, this group was attacked by the “Montgomery Volunteers,” a group of men Sheriff Daniel Hayes Candler of Rockville called together to stop the men from Charles County. These freedom seekers resisted, and around 30 managed to evade capture—unfortunately, Mark Caesar and Bill Wheeler were not among them.

Although Mark Caesar had been promised emancipation in 1844 by his enslaver, Port Tobacco planter John Barnes, he was tried as an enslaved man when arrested and faced conviction on “ten indictments for assisting ten slaves to runaway” in November 1845. Mark Caesar’s conviction resulted in consecutive sentences of five years each. He survived only five years in jail, where he died of consumption in November 1850 (Mark Caesar, 2011).

After Bill Wheeler’s conviction for the uprising, he initially received a death sentence by hanging. However, a special act of the Legislature ensured that he would have life imprisonment should his sentence be commuted—which the Governor did eventually. He managed to escape from jail, once again seeking freedom. It is unclear whether he eventually achieved freedom (William “Bill” Wheeler, 2010).

Both men faced trial at the Port Tobacco Courthouse and imprisonment at the Port Tobacco Jail, part of the Network to Freedom. Hear the full story of these two men and the Port Tobacco Escape from Charles County.

Belair Mansion (Prince George’s County)

Samuel and Anne Tasker Ogle owned Belair Mansion (c. 1745), beginning over a century of Ogle and Taskers calling the site home. At any one time, the Ogles held at least 50 enslaved people at the property. In addition to inventories that list the names, ages, and occasionally occupations of those enslaved, we know of several who tried to seek freedom.

The earliest known attempt was by a cook named Joe, who sailed on a boat to Philadelphia in 1744. A shoemaker named Tom escaped and may have found freedom in 1775 with the assistance of “some white people who make too familiar with [Ogle’s] slaves” (Explore Network to Freedom). In 1814, a different Tom left Belair with British soldiers—it is unclear whether he travelled with them or if he enlisted to gain freedom. The last known attempt occurred in 1852 by 27-year-old Dennis, although there is little information accompanying his runaway ad.

Riversdale House Museum (Prince George’s County)

Belgian immigrant Henri Stier built Riversdale, now a historic site owned by the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (M-NCPPC) in 1801. His daughter, Rosalie Stier Calvert, took over ownership when the Stier family returned to Europe, and the Calvert family maintained ownership for many generations.

Adam Francis Plummer was one of the many people enslaved by the Calverts at Riversdale. He married Emily Saunders in 1841 at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC, and they went on to have nine children together—despite the fact that they were enslaved at different plantations. In 1863, while enslaved at Woodlawn by the Thompson family, Emily decided to seek freedom in Baltimore with three of their older children and their twin toddlers, Nellie and Robert. The six freedom seekers did not make it to the city and were instead jailed. The Thompsons lacked the money to secure their release, and when Adam heard that his family was imprisoned in Baltimore, he received permission from Charles Benedict Calvert to retrieve them. Emily and the children arrived at Riversdale in December 1863.

The entire family was emancipated in 1864 at Riversdale, and the Network to Freedom now includes the site to commemorate Emily’s bravery. This is something that their daughter, Nellie, goes on to write about in her book, Out of the depths; or The triumph of the cross (1927):

No young woman of today can imagine the bravery that it took on mother’s part to venture to Baltimore alone, as it were, through troops of soldiers, during war time, with a girl of 11 years and a boy of 12, a girl 9 years, and two babies to be carried. Rut love knows no fear. We still think she was a heroine, indeed! (Plummer, 1927, p. 83)

Marietta House (Prince George’s County)

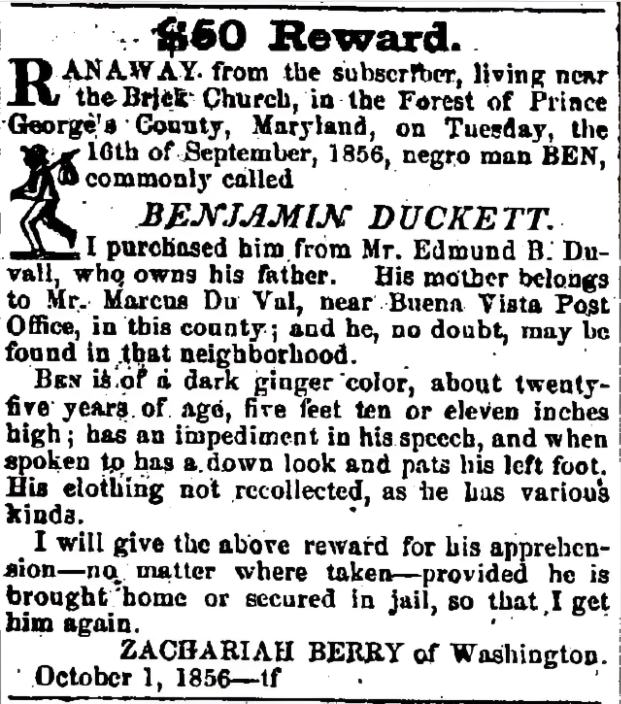

Marietta House, a tobacco plantation, was built by enslaved workers at the direction of US Supreme Court Justice Gabriel Duvall, who enslaved anywhere between nine and 50 individuals, including families of Ducketts, Butlers, Jacksons, and Browns. Freedom seekers born at Marietta, including Frank (last name unknown), Joe (last name unknown), and Benjamin Duckett, attempted to self-emancipate. These stories are what made Marietta House – also a historic site operated by the M-NCPPC – a part of the Network to Freedom.

Little is known about Frank, except that he left in 1814. In a runaway ad published by Gabriel Duvall in May 1837, Joe is said to have had two brothers, Tom and Phil. By 1837, Tom lived as a freeman in Baltimore, and it is likely that Joe would have attempted to reach this location (Duvall, 1837).

A few years later, in 1844, Gabriel Duvall passed away and his grandsons, Edmund and Marcus, divided Benjamin Duckett’s family and dispersed much of the enslaved population at Marietta. As a boy, Duckett would have observed many self-emancipation attempts by those in his community, including Joe. Zachariah Berry purchased and enslaved Benjamin Duckett from Edmund Duvall sometime between 1849 and 1856. Although the exact property where Duckett lived is uncertain – Zachariah Berry had properties in Washington, DC, and Prince George’s County – we do know that Benjamin Duckett left from Prince George’s County in September 1856 (Berry, 1856). He arrived in Philadelphia three weeks later, though his route is unknown. He was given a small amount of money by the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee so that he could continue his journey northward (Benjamin Duckett, 2017). It does not appear that Duckett was ever forced to return to Zachariah Berry, as three years later, Berry was still advertising for Duckett’s return—his reward had gone from $50 to $500 (Berry, 1859).

Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Museum (Baltimore City)

Freedom seekers often utilized the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad to achieve self-emancipation. A train was a riskier choice as there was a higher chance of recapture due to its crowded, public nature; this is why more covert methods of travel were often preferred, despite being slower. Henry “Box” Brown and the Craft family journeyed through the Baltimore station (the current site of the B&O Railroad Museum). Perhaps the most famous among these individuals, Brown, arranged to be shipped to Philadelphia via the Adams Express Company (which was known for both efficiency and confidentiality—they never looked inside the boxes they carried) (Robbins, 2009, pp. 12–13). After purposely burning his hand with sulfuric acid to avoid work that day, Brown managed to fit into a roughly 3x3x2 foot box to pose as dry goods. His full journey encompassed 27 hours of multiple wagon journeys, railway trips, and steamboat and ferry sailings to reach his destination, including passage through Baltimore. How much does it cost to seek freedom? For Henry “Box” Brown, $86 (or $3,414 in 2023) (Morris, 2011, pp. 15–17).

Mount Clare (Baltimore City)

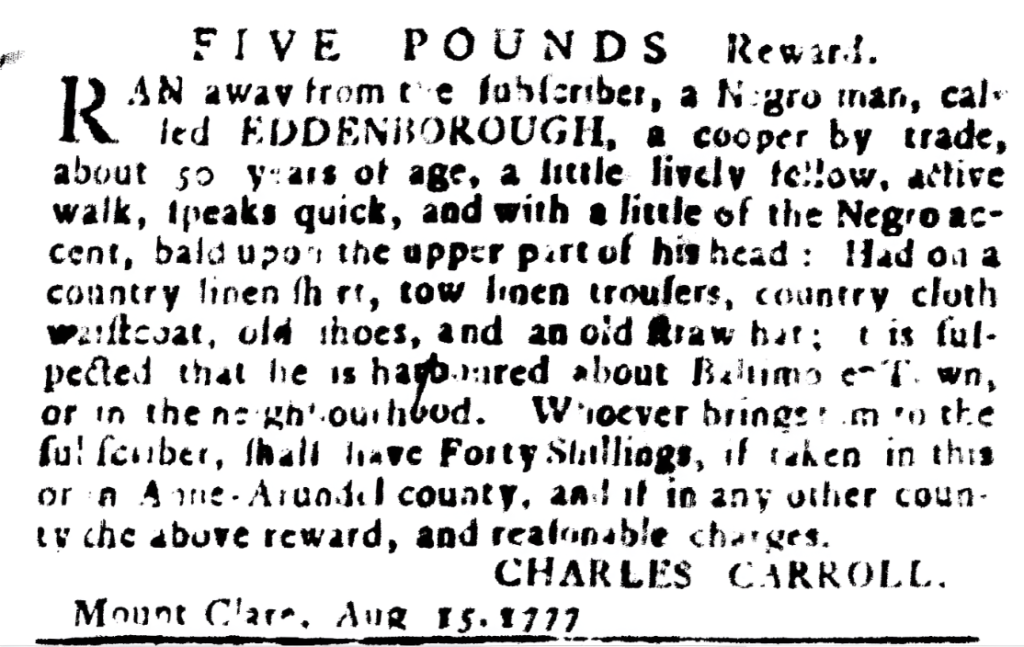

Built over 250 years ago, Mount Clare was originally an 800-acre plantation on the Patapsco River and housed the Baltimore Iron Works (one of the largest industrial undertakings of the colonial period). Both were owned and operated by Charles Carroll. Between the Mount Clare plantation and the Baltimore Iron Works, Carroll enslaved over 200 people. The enslaved workers at the Baltimore Iron Works had a wide range of skilled knowledge, with occupations such as blacksmith and hammerman (Slavery and Freedom in Maryland, 2007).

Situated only five miles from Baltimore, it is unsurprising that there were many attempts at freedom by the enslaved population throughout the 18th century. In 1777, when the iron works facility suffered from food shortages, a manager at the Baltimore Iron Works wrote that the “people and stock were almost starving” (Industrial Slavery, 2007). That same year, Carroll placed a runaway ad for the cooper Eddenborough (Carroll, 1777). In it, Eddenborough is described as having an accent, so it is possible that he was born in Africa. Assuming he went to Baltimore, Eddenborough would have had many options with the city’s growing free Black population and Philadelphia only a 40-mile journey.

St. Stephen’s African Methodist Episcopal Cemetery (Talbot County)

St. Stephen’s African Methodist Episcopal Cemetery in Talbot County serves as the final resting place for nearly 18 soldiers of the USCT, many of whom were originally enslaved at Wye Plantation. Their names are John Blackwell, Ennels Clayton, Isaac Copper, John Copper, Benjamin Demby, Charles Demby, William Doane, William Doran, Harace Gibson, Zachary Glasgow, Joseph Gooby, Joseph H. Johnson, Peter Johnson, Edward Jones, Enolds Money, Frederick Pipes, Henry Roberts, and Matthew Roberts.

Despite many objections by the Governor and other politicians, as well as slaveholding citizens, in 1863, the United States Colored Troops (USCT) began mass enlistments of Black men to fight for the Union. These men were often recruited directly from plantations in Maryland. One contemporary of Col. Edward Lloyd VI (owner of Wye Plantation during this period), wrote about the “boat loads” of enslaved men enlisting with USCT:

It appears that since we left the county [Talbot County] two week[s] ago, recruiting for the negro regiments have been going on with accelerated rapidity, and new vigor….I hear that Mr. Edward Lloyd, of Miles River neck, our largest slave holder, lost at One time as many as 84 able bodied hands and that enough have not been left to him “to black his boots…” (Wagandt, 1967, p. 135).

Before USCT conducted this mass recruitment at Wye Plantation, Matthew Roberts self-emancipated himself from Col. Edward Lloyd VI by using the local terrain to evade slave catchers. He then faked his own death and took a ferry to Baltimore, joining the 4th USCT (Mathew Roberts, 2014). Roberts, along with the other soldiers, found their own way out of enslavement through escape and military service. After the end of the Civil War, Roberts and the other members of USCT built a Black community, Unionville, just a few miles from the site of their original enslavement (Messner, 2020). St. Stephen’s serves as a place of remembrance for these soldiers and their descendants.

Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum (Calvert County)

According to the 1850 census, George Peterson enslaved 16 people at what is today known as Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum (JPPM). During the height of the Civil War, both William Coates (aged 18) and William Jones (aged 19) enlisted at Camp Stanton for a three-year term with with Peterson’s permission: a signed statement by Peterson showed that they were enslaved at his farm on the Patuxent River. During this period, any enslavers were compensated for allowing men to join the USCT (for example, Peterson received $300 in place of the labor Coates would have provided).

A private all through his service, Coates was enlisted in Company I of the 7th Regiment, while Jones rose to corporal in Company H of the 7th Regiment. We know both men were mustered out in Texas in October 1866. Coates returned to Calvert County where, by 1880, he married a woman named Rebecca and lived near the Peterson farm. We do not know what became of William Jones (Samford, 2021).

While MHT does not have an easement with JPPM, it is a state-owned museum for history and archaeology. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its 9,000 years of documented human inhabitation and the cultural diversity of the sites at JPPM (Patterson Archeological and Historic District, 1982).

There is always more to learn and explore about the Underground Railroad and the Network to Freedom. Created by the Maryland State Archives, the Legacy to Slavery database has an extensive digital collection of runaway ads, slave schedules, manumissions, and more. Medusa, MHT’s online database of architectural and archaeological sites, is a great way to fully explore any Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties sites and National Register of Historic Places properties in Maryland. You can also read past MHT blog posts about the underground railroad here:

References

B & O Transportation Museum & Mount Clare Station. (1961, September 15). National Register Properties in Maryland. LINK

Belair. (1977, September 17). National Register Properties in Maryland. LINK

Benjamin Duckett. (2017). Maryland State Archives. LINK

Berry, Z. (1856, October 8). Runaway Ad for Benjamin Duckett. Planter’s Advocate. LINK

Berry, Z. (1859, January 5). Runaway Ad for Benjamin Duckett. Planter’s Advocate. LINK

Carroll, C. (1777, August 19). Runaway Ad for Eddenborough. LINK

Certificate of Freedom for Towerhill (C290-1, Entry 51). (1809). LINK

Duvall, G. (1837, May 20). Runaway Ad for Joe. Daily National Intelligencer. LINK

Explore Network to Freedom. (2023). LINK

Holloway, J. E. (2005). Africanisms in American Culture, Second Edition. Indiana University Press.

Industrial Slavery—The Baltimore Iron Works. (2007). LINK

Marietta. (1994, July 25). National Register Properties in Maryland. LINK

Mark Caesar. (2011). Maryland State Archives. LINK

Mathew Roberts. (2014). Maryland State Archives. LINK

Messner, W. F. (2020). A Home of Their Own: African Americans and the Evolution of Unionville, Maryland. Maryland Historical Magazine, 115(2–3), 11–32.

Morris, R. V. (2011). Black Faces of War: A Legacy of Honor from the American Revolution to Today. Quarto Publishing Group USA.

Mount Clare. (1970, May 10). National Register Properties in Maryland. LINK

Our History—Sotterley. (2018, October 26). LINK

Patterson Archeological and Historic District. (1982, April 12). National Register Properties in Maryland. LINK

Plater, G. (1784, November 29). Runaway Ad for Clem Hill. Maryland Gazette. LINK

Plater, G. (1786, January 28). Runaway Ad for Towerhill. Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser. LINK

Plummer, N. A. (1927). Out of the depths; or, The triumph of the cross. Hyattsville, Md. LINK

Riversdale. (1973, April 11). National Register Properties in Maryland. LINK

Robbins, H. (2009). Fugitive Mail: The Deliverance of Henry “Box” Brown and Antebellum Postal Politics. American Studies, 50(1), 5–25.

Samford, P. (2021, February 11). Camp Stanton and the U. S. Colored Troops. Maryland History by the Object. LINK

Slavery and Freedom in Maryland. (2007). Mount Clare. LINK

Sotterley. (2000, February 16). National Register Properties in Maryland. LINK

St. Stephens African Methodist Episcopal Church. (2004). LINK

Wagandt, C. L. (Ed.). (1967). The Civil War Journal of Dr. Samuel A. Harrison. Civil War History, 13(2), 131–146.

William “Bill” Wheeler. (2010). Maryland State Archives. LINK

Port Tobacco Historic District. (1989, August 4). National Register Properties in Maryland. LINK