By Dr. Matthew D. McKnight, Chief Archaeologist

Inspired by a desire to celebrate and acknowledge Native American Heritage Day, I was approached by a few MHT staffers to write a blog post highlighting some of our work related to Indigenous cultures in Maryland. While the entire archaeology team is frequently involved in research projects that document the history of Maryland’s Indigenous peoples, I wanted to instead focus less on Indian identity as something “from the past” and instead put the emphasis on the continuum of Native American identity that stretches back through time.

“Canavest” by Dennis C. Curry – available now from MHT Press.

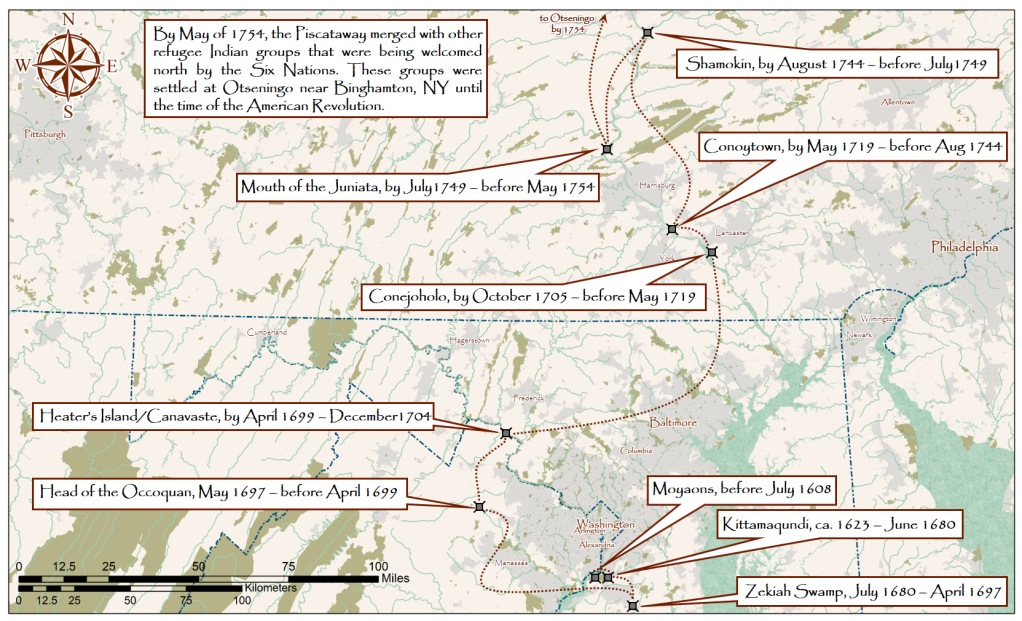

For the last couple of years, I have been involved in an effort by MHT Press to publish a significant volume highlighting the last permanent village of the Piscataway (also known as Conoy) Indians within Maryland. Canavest: the History and Archeology of a Late 17th Century Piscataway Indian Fort by former MHT Chief Archaeologist, Dennis Curry tells the story of a fort established on Heater’s Island in the Potomac River by the Piscataway Tayac (or principal chief), Ochotomoquath and his followers. The site was excavated in 1970 by the University of Maryland, but a detailed site report was never produced. Dennis spent the last several years of his career at MHT, meticulously scrutinizing the artifact collection and field records from these excavations to reconstruct what was learned about Piscataway life in the late 17th and early 18th centuries at this important site. Rico Newman, a prominent elder of the Choptico Band, Piscataway-Conoy Tribe of Indians, described the work as a portrayal of, “…the Piscataways’ remarkable survival and resilience during the onslaught of an advanced yet subversive Colonial government and its agents, while maintaining a semblance of traditional lifeways.” In keeping with that theme, I wanted to publish here some brief historical glimpses of that continued survival and resilience during the time period that followed the occupation at Heater’s Island.

The first thing to understand about the term “Piscataway” is that it has always referred to a confederation of Algonquian-speaking communities, rather than a single group. During the colonial period there were numerous Indigenous groups known by names such as Choptico, Mattawoman, Nanjemoy, Potapaco, Yaocomaco, Zekiah, and other names [1]. They all were part of the Piscataway confederacy of Maryland’s western shore, which were organized into an alliance and to some degree obligated to the Piscataway Tayac. Relations between the English colonizers and the Piscataway confederacy varied over time, but were generally friendly. Increasingly, however, encroachment by white settlers, the depletion of hunting territory, and insulting English accusations took their toll. The historical records suggests that many of the Piscataway people of the Late 17th century were using migration as a means to avoid problems with the English, eventually settling on Heater’s Island in the Potomac. While the Tayac and a large number of Piscataway did eventually leave Maryland altogether, there were also those who chose not to leave, or to fall off the trail of migration along the way and return to southern Maryland.

Both the colonial records of Maryland and Pennsylvania make it clear that by 1701, a large number of the Piscataway (increasingly referred to as the Conoys or Ganawese) were contemplating abandonment of Maryland for Pennsylvania. A Piscataway Indian named Weewhinjough (possibly the Tayac’s brother) was present at a meeting in Philadelphia on April 2nd, 1701 between several Indian leaders, the Council of Pennsylvania, and Proprietor William Penn in which both parties promised peace, loyalty to the Crown of England, and agreements were made regarding the English settlement of lands around the Susquehanna River [2, 3]. A few years later, the Piscataway abandoned Heater’s Island in December of 1704 due to a smallpox epidemic. At least 57 men, women, and children reportedly died in the epidemic and the following year, the Piscataway Tayac failed to present himself to the Maryland Governor to renew Articles of Peace with the English [4]. He may have succumbed to the disease and this is one of the last mentions we have of the Piscataway in the “official” records of Maryland.

While some of the Piscataway may have returned and stayed on at Heater’s Island until as late as 1712 [5, 6], a large contingent headed north into Pennsylvania. Some “Ganawense” from Maryland were established at a site called Conejoholo when Pennsylvania Secretary James Logan was visiting several Indian towns along the river in October of 1705 [7]. The “Canoise” are again reported in this location, 9 miles above Pequea, when Pennsylvania Governor John Evans visits the region in the summer of 1707 [8]. From there, the Piscataway/Conoy move farther and farther north and then west during the 18th century. They make one of their last appearances in the historical record in 1793 in Ohio when the Conoy, along with several other Indigenous nations sign two letters demanding that the Americans honor British agreements setting the Ohio River as the southern and western boundary of Indian lands [9]. Their pleas were ignored, and the Battle of Fallen Timbers followed a few months later.

Map of Piscataway Migrations from The Archaeology of Colonial Maryland: Five Essays by Scholars of the Early Province – available from MHT Press.

But that is certainly not where the story of the Piscataway ends. While the Piscataway as a named Indian community disappear from historical records, during the 19th and 20th centuries there are consistent whispers of a distinct community of people living in southern Maryland that insisted upon their “Indianness”. This story is more fully fleshed out in the excellent book Indians of Southern Maryland by Rebecca Seib and Helen Rountree, but by as early as the 1880s (basically around the time that the field of Anthropology was forming…and anyone began asking), there were reports of individuals in southern Maryland claiming to have Native American ancestry. In an early report of the American Anthropologist (only the second year of the journal’s existence), Elmer R. Reynolds provided a detailed account of his expedition to examine the shell middens at the mouth of the Potomac River. In his article, he relays that he was led to these sites by an individual named “Swann” who claimed native ancestry [10]. Not long after, the Smithsonian Institution took an interest and began requesting information from local medical doctors, court judges, and other officials related to a community in the area that claimed Indian ancestry and practiced endogamous marriage [11].

This community lived predominantly in Prince George’s and Charles Counties in the area around Oxon Hill, Waldorf, LaPlata, Bryantown, and Chaptico, and consisted of folks with the surnames Butler, Gray, Harley, Linkins, Mason, Newman, Proctor, Queen, Savoy, Swann, Thompson, and a few others [12, 13]. The terms used by researchers to describe this community changed over time. In “official” government records they were often listed simply as “colored” which says more about the forced racial designations on government paperwork at the time than anything about how members of the community identified themselves. Parish records sometimes provided additional detail, and there are several accounts of individuals with these surnames proclaiming their Indian identity, as well as advocating for their own local schools (this during the period of segregation) or their own facilities in churches and other public buildings. Catholic parish birth, marriage, and baptismal records were detailed enough so that researchers like Paul Cissna and Rebecca Seib were able to determine that these families were, in a majority of cases, actively seeking marriage partners from within the community who identified, like them, as Indigenous [13, 14]. From the period of 1757 until the 1950s, upwards of 70% of the marriages were between individuals within this community and not with individuals with outside surnames. Typically these marriages were arranged by female elders, suggesting a continued emphasis on the importance of matriarchy among the Indians of southern Maryland [14, p. 171].

In addition, certain distinctive practices were kept alive. One of the most important was the Green Corn festival celebrated during the two weeks surrounding August 15th. In the 19th and early 20th centuries this event typically took the form of a prolonged family reunion, with several nights of community dinners and games, horseback races, as well as socializing and celebration of the harvest. By the 1930s, conflicts with church authorities who wanted to shift emphasis to the entire non-Indigenous congregation and the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (held on August 15), led to decline in the practice [14]. However, by the late 1940s and into the 1950s, the pan-Indian pow-wow celebration would emerge in the region as a more overt expression of Native American identity, with the first being held in Washington, DC in 1949 [14, p. 176].

Increasingly, over the course of the 20th-century, voices from within this community began to speak out more publicly about their Indian (and increasingly Piscataway) identity. One of the most prominent leaders to emerge during this period was Philip Sheriden Proctor, also known as Turkey Tayac. Tayac was a veteran of the first World War and active in eastern states veterans organizations. He used connections he had within these wider organizations and with federal institutions to seek out others in the wider Native American community with whom he could find common cause. A traditional herbalist, Turkey Tayac appears to have always been outspoken about his Indian identity and began encouraging others within the southern Maryland community to speak out and to start taking steps towards formally organizing. This process really began getting underway in the 1970s [14, p. 176].

Though Turkey Tayac would not live to see it (he passed away in 1978), he helped to lay a groundwork that eventually led to formal recognition of the southern Maryland tribal community by the State of Maryland. Though there were setbacks along the way, Governor Martin O’Malley issued an executive order on January 9th, 2012 formally recognizing two groups: the Piscataway Indian Nation and the Piscataway-Conoy Tribe [15]. When one considers all of the shifting cultural, socio-political, and legal forces stacked up against that moment taking place, there is no word that more aptly describes the Piscataway peoples of Maryland than “resilient”. Despite the loss of Indigenous lands and language, government interventions to break up traditional leadership and kinship structures, and outside religious and social forces that sought to suppress Indian identity, Piscataway people have found ways to persevere and to stand up and say I am Indigenous and I am here. Today, we celebrate that perseverance.

Works Cited

1 – Maryland

2022 “Native Americans.” In Maryland at a Glance. The Maryland State Archives, Annapolis. Available online at https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/01glance/native/html/01native.html.

2 – Browne, William H., Edward C. Papenfuse et. al. (editors)

2018a [1701] Assembly Proceedings, May 8-May 17, 1701. Reproduced in Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, April 26, 1700-May 3, 1704. Originally published 1883, ongoing, Archives of Maryland, 215+ volumes, Baltimore and Annapolis, Volume 24, p.145-146.

3 – Pennsylvania

1852 [1701] Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, from the Organization to the Termination of the Proprietary Government. Volume II. Jo. Severns & Co., Philadelphia, p.14-19.

4 – Browne, William H., Edward C. Papenfuse et. al. (editors)

2018b [1701] Proceedings of the Council of Maryland, 1705. Reproduced in Proceedings of the Council of Maryland, 1698-1731. Originally published 1883, ongoing, Archives of Maryland, 215+ volumes, Baltimore and Annapolis, Volume 25, p.187.

5 – Curry, Dennis C.

2014 “We have beene with the Empeour of Pifcattaway, att his forte”: The Piscataway Indians on Heater’s Island. Presentation at the 2014 Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference, Langhorne, PA.

6 – McKnight, Matthew D.

2019 “The Piscataway Trail: Clues to the Migration of an Indian Nation.” In The Archaeology of Colonial Maryland: Five Essays by Scholars of the Early Province, edited by Matthew D. McKnight, pp. 174-181. The Maryland Historical Trust Press, Crownsville.

7 – Pennsylvania

1852 [1701] Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, from the Organization to the Termination of the Proprietary Government. Volume II. Jo. Severns & Co., Philadelphia, p.244-247.

8 – Pennsylvania

1852 [1701] Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, from the Organization to the Termination of the Proprietary Government. Volume II. Jo. Severns & Co., Philadelphia, p.386-390.

9 – Curry, Dennis C.

2011 “A Closer Look at the “Last Appearance” of the Conoy Indians”. Maryland Historical Magazine 106 (3): 345-353.

10 – Reynolds, Elmer R.

1889 The Shell Mounds of the Potomac and Wicomico. The American Anthropologist 2(3): 252-259.

11 – Mooney, James

1889 Answers to Mooney’s ‘Circular’ from Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, and North Carolina, 1889-1912. MS 2190. Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropologial Archives.

12 – Seib, Rebecca and Helen C. Rountree

2014 Indians of Southern Maryland. The Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore.

13 – Cissna, Paul B.

1986 The Piscataway Indians of Southern Maryland: An Ethnohistory from Pre-European Contact to the Present. Ph.D. Dissertation. The American University, Washington, DC.

14 – Seib, Rebecca and Helen C. Rountree

2014 Indians of Southern Maryland. The Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore.

15 – Dresser, Michael

2012 “O’Malley formally recognizes Piscataway tribe”. The Capital Gazette. Available online at https://www.capitalgazette.com/bs-md-omalley-tribes-20120109-story.html.

Are there any records of locations of burial grounds? I’m actually looking to trace trauma through maps.

Hi Elizabeth. I am aware of no specific records about burying grounds, but undoubtedly the various communities shown on my map of Piscataway movements in the blog post would have had associated burials. People tended to be buried not far from where they lived.