By Annie Allen, Architectural Survey Data Specialist

This time last year, as a new employee of the Maryland Historical Trust, I attended my first annual all-staff meeting at the beautiful Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum (JPPM). The day included a fun “Mystery Heist” icebreaker, for which we all assumed the personalities of various characters who frequented the Patterson residence in the 1950s. When I was assigned my character – Gertrude Sawyer, the architect of the park’s Point Farm – I was instantly intrigued. Gertrude Sawyer happens to be my mother’s name! To get into my role, I read a small synopsis about Gertrude and learned that she was from Tuscola, Illinois, two hours away from where my Sawyer ancestors hail. These coincidences spurred me to dig a little deeper to find out more about this woman. I was hoping to find a fun family connection to my assigned character. What I discovered is definitely worth sharing.

Gertrude graduated from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1918 with a B.S. in landscape architecture. Wishing to be an architect from a young age, she attended Smith College’s Cambridge School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, where she earned a Master’s in Architecture in 1922. She then moved to Washington, D.C., to work as an associate for Horace W. Peaslee – however, not before building and selling her first residential home in Kansas City, Missouri. She received an early commission while working for Mr. Peaslee to design the Junior League of Washington’s Art Deco headquarters on Dupont Circle. In 1934, Gertrude opened her own firm and became an AIA member in 1939. During World War II, Gertrude helped to design four thousand temporary homes for military families in D.C. She earned the rank of Lieutenant Commander for the Navy’s Civil Engineer Corps (the Seabees). By the time of her retirement in 1969, Gertrude was registered to practice architecture in the District of Columbia, Ohio, Florida, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

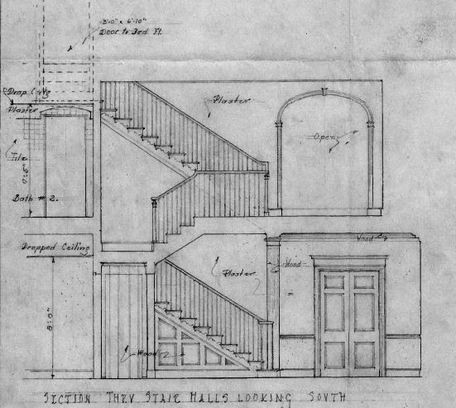

Gertrude’s projects were predominantly residential, with a focus on country estates. In 1932, Jefferson Patterson, a foreign service diplomat, hired Gertrude to design Point Farm, his country residence in St. Leonard, Maryland, most of which is now JPPM. This project resulted in 26 building designs, ranging from an elegant Colonial Revival family home and guest houses to a show barn for cattle. The Patterson family considered Gertrude the family’s architect. Gertrude’s scrupulous eye for detail is not only evident in the exquisite classical architectural features of the Patterson home but also in her rigorous note-taking, sections, and plans. Her drawings can be found online at the Maryland State Archives, and many of her building designs can still be seen around Maryland and the Washington, D.C., area.

As one of this area’s early woman architects, Gertrude Sawyer was definitely a groundbreaker in her field. However, rather than being recognized as a female architect, she preferred to be known as a good architect. In an interview with Gertrude, Matilda McQuaid revealed “that several women’s organizations had contacted her, knowing her to be one of the pioneer women architects. But when she told them, ‘I was always treated fairly, and throughout my career had a very good time building and designing,’ they never called back.” She once told the Sunday Star that “[p]eople who don’t want a woman architect just don’t come to you. But others see the advantage of your being able to interpret their individual needs because you are a woman.” Gertrude’s dedication to her profession and her pursuit of excellence forged a successful career with many long-standing clients like the Pattersons.

Although I haven’t found that family connection yet, it was a pleasure ‘getting to know’ this accomplished architect and trailblazer. I’m still researching!

For more information about Gertrude Sawyer’s buildings at Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum, visit https://jefpat.maryland.gov/Pages/default.aspx

Sources:

Allaback, Sarah. The First American Women Architects. University of Illinois Press, 2008.

American Institute of Architects. Application For Membership. June 1939. Gertrude Sawyer’s AIA Application. 1735 New York Ave. NW, Washington, DC.

Berkeley, Ellen Perry., and Matilda McQuaid. Architecture: A Place for Women. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1989.

Dean, Ruth. “For The Seabees: Woman Architect Came to Their Aid.” The Sunday Star [Washington. DC] 25 Mar. 1956, D-10 sec.: n.

“Early Women of Architecture in Maryland.” http://www.aiawam.com/.